How a Tree Kangaroo Saved the Rainforest

Translation of the Trouw newspaper, original article written by Anne Broeksma, published on the 30th of October 2019.

In the cloud forests of northern Papua New Guinea, lives the heavily hunted Scott’s tree kangaroo. This animal became the key to protecting the rainforest.

He looks a bit like a small bear with a long tail. He chews ferns and vines in the crown of forest giants. Only when he comes down does his true nature become visible as he hops over the mossy forest floor to the next tree. Just like a kangaroo. It is a Scott’s tree kangaroo, called Tenkile by the locals.

In 2003, when the Australian couple Thomas was told that there are only a hundred Tenkiles left in the wild, the couple stopped their work at the Melbourne Zoo. The Tenkile Conservation Alliance (TCA) was founded and they moved to the remote Torricelli Mountains in northern Papua New Guinea. Within two years, the Tenkile, which lives nowhere else outside the western part of that specific rainforest, must be rescued from extinction.

In the beginning, a successful outcome was still unthinkable.

“A few years before we arrived, thirteen villages in the area had signed an anti-hunting treaty. However, the villagers told us without hesitation that they had caught a Tenkile last month. They are so poor here that they sign every contract that is submitted to them, hoping to benefit from it.” – Jean Thomas

Missionaries

The conservationists who had previously come by had no arguments that appealed to the population. Furthermore, they offered nothing in return to the hunting ban. Jean and Jim soon realised that their ecology lessons did not work in practice. In the end they mainly talked and listened during the first period of their stay.

The oldest generation appeared to know stories about the Tenkiles in which their place in local cosmology was named. However, these stories were largely forgotten. According to Jean, this is partly due to the work of Christian missionaries. Traditionally, the forests were sacred and bewitched places, where hunting was not permitted and therefore it was an animal refuge. Missionaries, in their fight against superstition, went through these areas, blessed them and declared them neutral. “So, the villagers thought, now we can hunt everywhere.”

From the stories of the elderly, it proved that the Tenkile had the special status of the first created animal. Supreme god Yani created the Tenkile and only afterwards the other tree kangaroos and forest animals. Every tree kangaroo received its own habitat. The Tenkile, timid in character, was only allocated to the western part of the Torricelli mountains.

The interest of Jean and Jim Thomas in the stories and songs about the Tenkile ensured that the marsupial was reinstalled in their culture and became a local mascot.

“The relationship with the Tenkile also distinguished these villages from the villages in the east, where the equally endangered golden-mantled tree kangaroo lives. Those villages started to identify with ‘their’ tree kangaroo, locally called the weimang . In the end there was an alliance of twenty Tenkile villages and thirty weimang villages.” – Jean Thomas

In five years, the population of Tenkiles grew from one hundred to three hundred individuals. But the impact of the project has been much greater. Now, after nearly seventeen years of intensive work, in an area of 185,000 hectares, hunting has stopped and the inhabitants of fifty villages work together to protect the forest.

The alliance that Jean and Jim managed to form with fifty villages required more than a new mascot. They also had to offer alternatives to hunting. They introduced a rabbit farming project, to breed rabbits as an alternative source of protein. They also helped with a better distribution of trade crops such as cocoa and vanilla. Thanks to new funds, toilets and water tanks were installed in the villages.

In fact, most of the work was focused on people, not on animals.

“In all those years I have only seen a tree kangaroo twice. In the beginning, we collected some tracks and placed trail cameras, but soon social work turned out to be much more effective. If the level of education rises, people no longer want to sneak through the jungle all night to catch one animal. It is much more attractive to play a social or political role in the village. ” – Jean Thomas

Mining Companies

In the meantime, the external threats to the Torricelli mountains have also become apparent. Malaysian timber companies cut timber illegally along the edge of the area, and mining companies empty the forest under the guise of ‘exploration research’. That is why in 2004, Jean and Jim started to think about what their biggest challenge in Papua New Guinea was: Ensuring that the area is effectively protected.

“Officially, the Torricelli mountains already had protected status, but in practice that meant nothing. The problem is that large nature organisations bring out a map, draw a line and say, “This is a protected area.” That has no effect on the ground.” – Jean Thomas

Jean and Jim decided to take a more thorough approach. Because there are hardly any roads in the Torricelli mountains, they walked along the edges of the mountains, accompanied by delegations from the Tenkile and the weimang villages and armed with a GPS, a notebook, a photo camera and the knowledge of the villagers.

“We have recorded every point that was important to them or defined a boundary between one tribe and the other. We were often surprised. We saw a tree like any other, they saw a tree that was planted five generations ago by an ancestor. All stones, intersections and rivers were found to have meaning. We see a stone; they see their history.” – Jean Thomas

The work of Jean and Jim gained momentum this year by the appointment of a new environment minister. The government of Papua New Guinea is expected to provide the final stamp within three months. Then the borders with their corresponding rights will be assigned. The large impact is clear from the death threats they receive from the mining and logging companies. However, Jean and Jim cannot be stopped.

“The definition of rights and processes, together with the people who live there, is what good forest management is all about. Without the tree kangaroo we could not have done it. Only with a good story can you protect a forest.” – Jean Thomas

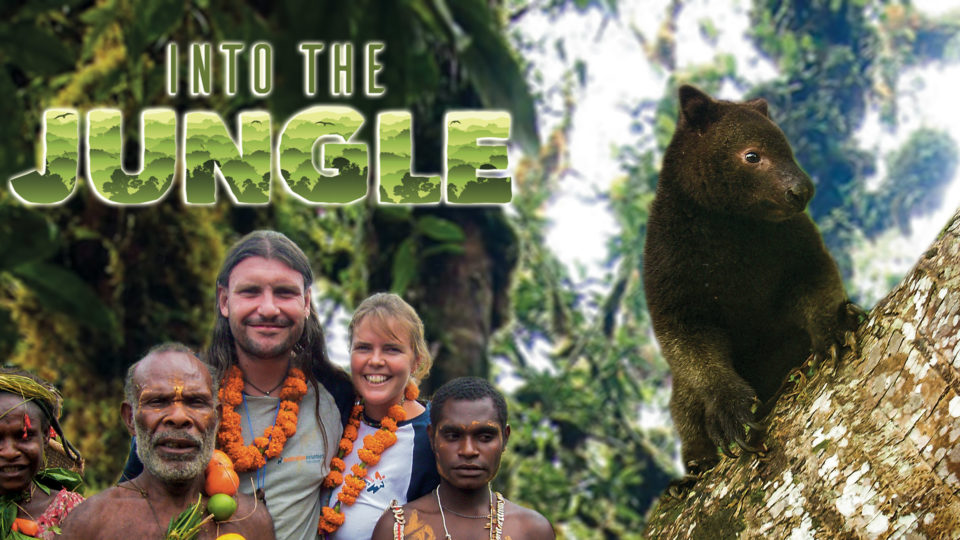

Wildlife Film Festival Rotterdam

The documentary ‘Into The Jungle’ was made about how Jean and Jim Thomas approached the protection of the tree kangaroos, which was screened on 2nd and 3rd of November 2019 during the Rotterdam Wildlife Film Festival. Jean and Jim received many prizes for their distinctive form of nature conservation, including the Future For Nature Award 2010, in Burgers’ Zoo.