Protecting the Mysterious Himalayan Wolf

Translation of the Trouw newspaper, original article written by Anne Broeksma, published on the 18th of November 2019.

The Himalayan wolf as “grey wolf” has the status of “not threatened”, but evidence is indicating otherwise.

Wolf researcher Geraldine Werhahn is fighting to get the Himalayan wolf recognized as a separate lineage of wolf. That is also the only way to ensure that the rare animal receives appropriate protection status. Now the wolf is typically seen as a cattle thief by farmers in the high mountains.

When biologist Geraldine Werhahn (34) went to Nepal in 2012, she was on a holiday. During a hike through the Himalayas, she inquired about wolves out of curiosity. Farmers tell her that they are higher up in the mountains, but even when she reaches the snow line, she can’t find a trace. Once back home, little appears to have been published about the wolves. They remain a mystery.

Earlier, during her studies, she studied wolves in Montana and lynxes in her country of birth, Switzerland.

“I knew early on that I wanted to study and protect large predators. Being on top of the food chain, they balance the entire ecosystem. They literally let nature bloom.” – Geraldine Werhahn.

Credits: Naresh Kusi

Later she comes across a study about Tibetan mastiffs. The strong, woolly dogs that have been living for thousands of years in the Himalayas appear to have modifications in their genes for life in high-altitudes. They might have received those modifications through crossbreeding with wolves. This makes her even more curious and she decides to search for the Himalayan wolves.

In 2014, she sets up her first expedition with Nepalese fellow researcher Naresh Kusi. Together with a cook, a local guide and a procession of mules, they spend two and a half months between 3000 and 5500 meters in the isolated Humla district in Nepal. There, Werhahn sees her first Himalayan wolf: “In the distance I saw a dark, almost black wolf, moving from one side of the plateau to the other with such a typical wolf walk – this energy-saving trot -. He was watching me, not impressed. But I was.” The Himalayan Wolves Project was born.

Since then, Werhahn and Kusi have been staying in the high mountains of Nepal and China for a few months each year. They know how to follow different small wolf packs and together they walked 1800 kilometres through endless alpine meadows, along stony plateaus and over snowy mountain tops.

“We learned to read the landscape like a wolf and slowly started to behave like a wolf pack”. – Geraldine Werhahn

Along the way they collected data in the form of droppings and tufts of hair. They contain clues about their diet, but also about the evolutionary history of the Himalayan wolves. Through genetic research they discover that the wolves above 4000 meters, even more than dogs, are completely adapted to their environment. “The air you breathe up there, contains 50 percent less oxygen than air at sea level. Yet the wolves have no problems with that. They have genes that support stronger heart function and a more efficient blood circulation, which causes the oxygen to be transported better through their bodies.”

“Genetically even the average domestic dog has more similarities with the grey wolf”

According to Werhahn, the evolution of the Himalayan wolf is so different that it is time to recognize it as a separate wolf: “You don’t see it on the outside, but genetically even the average domestic dog has more similarities with the grey wolf.”

It is not the first time that a new kind of wolf species has been described. In 2015, scientists discovered that the African golden jackal actually is a wolf. Under the influence of the habitats where they live, they have started to look like the Eurasian golden jackal. Smaller and slimmer than you would expect from a wolf, with a thinner coat.

“In many animal species, outer differences are fairly indicative of species, but that is not the case with a wolf. A wolf comes in many forms. ” – Geraldine Werhahn.

The wolf of the Himalayas may have a special evolutionary story, but he is not popular. The farmers in the mountains of Nepal, Tibet and China see the wolves mainly as livestock thieves. The wolves get cubs in the spring, the time when the farmers let their yaks, cows, and sheep graze in the meadows higher on the mountains. “That wolf mother comes out of her den and the green field is suddenly filled with yaks. The prey that she normally prefers to hunt, such as blue sheep and Tibetan gazelles, flee from this invasion. Her cubs are hungry. Of course, she will sometimes grab a yak calf. ”

“The tongue of wolves is sold as medicine to soothe a sore throat”

In response, farmers sometimes go to the denning caves where the cubs are hidden. They light a fire and close the entrance, and the cubs choke to death in the smoke. Another problem is the illegal wildlife trade: “In China there is a market for almost every part of every wild animal, including wolves. Their tongue is sold as medicine to soothe a sore throat. And some Chinese believe that you are lucky during card games when you store four wolf legs and a wolf skull in your home.”

What also does not help is that dogs have a lower status in Buddhism and Hinduism compared to cats. The other top predator of the area, the snow leopard, is seen as an icon of the high mountains and has been actively protected for decades. “The Dalai Lama has said that Buddhists should not kill snow leopards. That made a huge impact.”

The fact that Werhahn thinks that the Himalayan wolf merits recognition as a separate wolf is based on the scientific evidence and this is also crucial for their conservation. As a ‘grey wolf’, he has the status of ‘not threatened’ at the IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature. If the Himalayan wolf is recognized, it is likely that its status will be ‘threatened’ based on population estimates.

Letter to the Dalai Lama

With her field study of the Himalayan wolf Werhahn has completed her PhD at the University of Oxford. In 2018, she received the Future For Nature Award in Burger’s Zoo for her distinctive work. She will use the prize money to work with the local community to prevent conflicts between farmers and wolves. “Special areas can be designated where the cattle are not allowed to graze. When wild prey gets space, a wolf is less likely to grab a sheep or yak. And with fences and sheepdogs, farmers can better protect their cattle. The farmers are open to our ideas, because if they lose an animal to a wolf, it affects them financially.”

This spring, Werhahn will return to the roof of the world to work on the solutions. “But first I will write a letter to the Dalai Lama.”

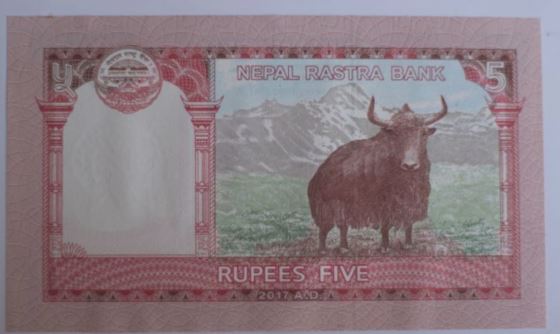

Wild yak was also (re) discovered

During a wolf expedition in Humla in 2015, a six-day walk from civilization, Werhahn sees a black dot in the distance. The team manages to get closer by taking a detour and stands face to face with a wild yak. As a great ancestor of the domesticated yak, it is an iconic animal for Nepal, but at that time it had not been observed within the national borders for more than fifty years. Werhahn and Kusi manage to take a picture of the giant, long-haired cow. A wave of excitement goes through Nepal and the team’s photo of the wild yak has been on the bank note of the 5 Nepalese rupees since 2017. Whether it is seasonal migration from Tibet or a definitive return is still unknown.

Since 2017, Werhahn’s photo of the wild yak her and her team have rediscovered appears on the bank note of 5 Nepalese rupees.

Credits: Geraldine Werhahn