Saving Bats in Wartime: The Impact of the FFN Award

Bats are facing numerous challenges nowadays. They are threatened by climate change, collisions with wind turbines, loss of habitat, decreasing insect population (which is bats’ main diet), fungal disease and chemical poisoning. Most of these factors are caused by humans.

Luckily, in many countries people are already taking responsibility to conserve bats. The trend of bat population decrease across Europe, observed in the first half of the 20th century, seems to have been overcome. Bats are recovering, while more and more people learn how to co-exist with them without harming their habitats and migration routes. Since 1993, the European Environment Agency has observed an increasing number of 16 bat species (out of 48) across the continent. It means that the conservation policy worked out. Governmental actions, plus international agreements like Eurobats (Agreement on the Conservation of Populations of European Bats), succeed in preserving bat species. Moreover, numerous local bat rehabilitation centres across Europe take immediate action to save bats every day. The biggest centre of Eastern Europe is located in Ukraine. Ukrainian Bat Rehabilitation Centre (UBRC) has already rescued more than 35,000 bats.

Bat rescue and rehabilitation

Fifteen years ago, Alona Prylutska, co-founder of the UBRC, began the project to rescue bats found on the ground, in window and balcony traps, and other urban habitats. Bats simply find these spots convenient to roost for the winter after migrating in autumn.

During construction works, people find colonies of bats in such spots and don’t know what to do with them. The bats were often thrown away, but since the Rehabilitation Centre opened, people can call to report finds. UBRC picks up the bats to rehabilitate and releases them in the spring.

Each year, the number of these reports is increasing. The Centre received 862 bats in 2012 and 6,042 in 2022, which is more than seven times as many. Until recently, the Centre could only accommodate up to 3,000 bats.

Long-eared bat in the Rehabilitation Centre.

Impact of the FFN Award

In 2023, Alona won an FFN Award. It was one of the biggest factors that helped the Centre continue rescuing bats under the war circumstances. The FFN Award brought foreign attention to the UBRC, and similar bat rehabilitation centres got in touch with the Ukrainian one. It inspired Alona’s team to continue, because now bats need their help even more than ever.

UBRC is located in Kharkiv, 20 kilometres away from the border with Russia. Kharkiv was and still is being heavily bombed. It’s not possible to estimate how many bats died in the fallen constructions. Due to the front-line areas being inaccessible for bat monitoring, and we know that these areas were home to bat colonies before the war, the partial or total destruction of Ukrainian towns could mean thousands of bat deaths.

Next to facing the war personally, the UBRC team has to deal with the increased number of bat colony finds. Placing over 6,000 bats during one year in a couple of fridges, feeding them, and providing them with medical care is a truly challenging task, especially when UBRC mostly relies on charity funding. Public attention naturally shifted from bat issues to mere survival. This created an urgent need for any help available, so Alona applied for the FFN Award.

Alona at the FFN Awards, which she won in 2023 (photo by Robert Meerding).

The FFN Award came at a crucial moment. The funding helped Alona and her team relocate the UBRC office to the basement space, which is much bigger and safer than the previous office. UBRC also bought a car; previously they had to rely on public transport or tried to find volunteers with personal vehicles.

Moreover, FFN funding helped purchase additional refrigerators, including for equipping volunteer centres across the country. The Centre now has eight of them for bats’ hibernation. The next step is going to be creating a separate hibernation room. Right now, it’s the team’s dream, and more funding is needed. But given UBRC’s work to build the best conditions for rescuing bats and the growing support from international partners, it could become possible soon.

Creating new homes

One of Alona’s goals for FFN funding was to create and distribute concrete bat boxes as alternative roosts for bats. UBRC has recently begun building those boxes. They mimic tree hollows and building crevices, serving as an additional roost option for species that normally use tree cavities. Alona’s team is placing these boxes around the country to create enough spaces for bats to settle.

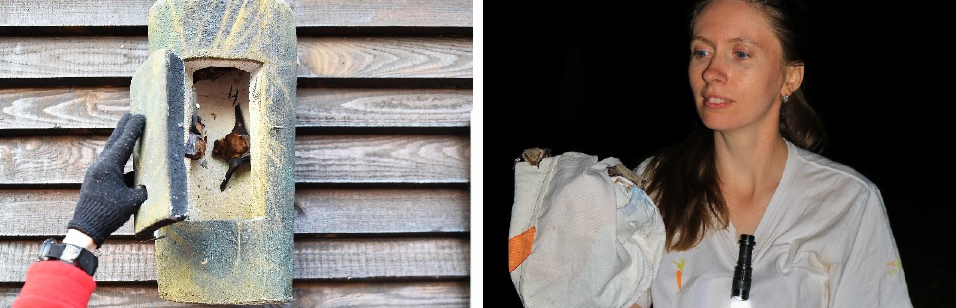

Left: Bat boxes are offered as alternative roosts for the bats. Right: Alona releasing rehabilitated bats.

Next to creating alternative roosts, Alona wants to set up a “shared house” project. The project aims to cooperate with building companies to prevent house-dwelling bat mortality and bat disturbance during building renovations. Alona’s team is going to train the State Emergency Service of Ukraine team on how to handle bats. The training will take place in Dnipro city, which is not far from the frontline.

New partnerships

The biggest goal that was set for the FFN Award was to launch more branches of the Bat Rehabilitation Centre. Now, UBRC partners with governmental establishments (city council, museums, zoo, national parks and reserves), NGOs and volunteers in Kyiv, Rivne, Odessa, Lviv, Zaporizhia, Dnipro, Poltava, Vinnytsia, and Uzhhorod. More and more people want to volunteer, which gives hope that fewer people will stay sceptical about bats. Alona’s team regularly organises online and in-person events on how to interact with bats, debunks myths (like the idea that bats are deadly dangerous), and Alona co-wrote a freely accessible manual on bat rehabilitation.

The FFN Award gave the Ukrainian Bat Rehabilitation Centre the tools and recognition it needed to keep saving bats during wartime and even scale the project. With more fridges, a safer office, and stronger international partnerships, the team can continue its mission even under daily challenges.

In the end, the award did more than provide funding. It helped prove that even in times of war, conservation is possible, and that protecting bats is protecting biodiversity, a reminder that resilience is vital for both people and wildlife.

Written by Darina Khyzhko